Archivo abril 2018

Estas serán las presentaciones y rutas de ‘Pirenaica’

Este es el calendario de las presentaciones del libro ‘Pirenaica’.

2 de mayo (19:30): BARCELONA, en la librería Altaïr (Gran Vía, 616). Presenta Dante Hermo.

(6 de mayo: RUTA DE LOS ESCLAVOS. Haremos un recorrido en bici, o en el vehículo que queráis, por una parte del primer capítulo del libro. Los detalles, al final de esta entrada).

9 de mayo (19:00): SAN SEBASTIÁN, en la sala de actos de la Biblioteca Municipal (entrada por la calle San Jerónimo, Parte Vieja). Presenta Ruth Pérez de Anucita.

10 de mayo (18:30): BILBAO, en la librería Elkar de la calle Poza (c/ Licenciado Poza, 14). Presenta Dante Hermo.

15 de mayo (19:00): PAMPLONA, en la librería Katakrak (calle Mayor, 54). Presenta Danielito Burgui.

17 de mayo (18:30): VITORIA, en la librería Elkar (c/ San Prudencio). Presenta Álex Ayala.

*

Domingo, 6 de mayo: RUTA DE LOS ESCLAVOS

Recorreremos una parte del primer capítulo del libro: las carreteras construidas por presos del franquismo entre 1939 y 1945. Pararemos en algunos puntos interesantes.

El itinerario tiene 62 km y varias subidas exigentes (Arkale, Elurretxe-Castillo del Inglés y Jaizkibel), así que hace falta un poco de nivel ciclista para completarlo a pedales. Si alguien quiere acompañarnos en moto, coche o globo aerostático, será un placer -y si trae pan y jamón para las paradas, placer doble-.

(AVISO: en la parada de Arkale vendrían bien unas zapatillas para caminar, mejor que las de ciclista, aunque tampoco es un camino largo. Yo, por ejemplo, llevaré unas chancletas en mi bolsita del manillar y ya está).

HORARIO TRANQUILO Y APROXIMADO:

8.45. Donostia. Encuentro en el alto de Miracruz. Explicación de la ruta y las paradas.

9.00. Salida. Pasai Antxo, Errenteria, polígono industrial Lanbarren, subida a Arkale.

9.45. Búnker de Arkale, que era el destino militar al que debía llegar esta carretera construida por los presos republicanos. Hay que caminar unos pocos metros por el bosque y meterse por una galería subterránea de hormigón.

10.15. Seguimos. Barrio de Gurutze -vistazo a la casa Galdosenea- y cruce hacia el Castillo del Inglés-Elurretxe.

10.30. Campamento Babilonia. Un vistazo a los escasos restos del campamento de los presos. Panel informativo.

11.00. Fusilamientos de Pikoketa. Placa junto al caserío.

11.30. Collado de Elurretxe, monte Erlaitz: restos del fuerte.

12.00. Irun.

12.30. Fuerte de Guadalupe, otro destino militar que justificó la construcción de una carretera absurda -y tan bonita- con mano de obra forzada.

13.00. Alto de Jaizkibel. Venga, que ya es todo para abajo.

13.15. Erroteta. Barracones y otros edificios de los presos. Placa y panel informativo.

13.45. Donostia.

1Publico un libro a pedales: ‘Pirenaica’

Publico un libro viajero y ciclista: ‘Pirenaica’, catorce etapas de mar a mar, catorce crónicas de la cordillera.

La editorial Geoplaneta ha colgado aquí el primer capítulo, por si queréis leerlo.

Encontraréis montañas medio mágicas y hombres medio osos, un pueblo de pescadores chiflados y un Tour sin un solo cuerdo, una aldea cubista y un viento surrealista, osos eslovenos y peregrinos coreanos, una guerra que empezó por una señal de Stop y otra que acabó por tres vacas, monstruos tímidos y camareros gruñones, un país enano entre montañas gigantes, emperadores enamorados y condesas pelirrojas, héroes de mentiras y esclavos de verdad. (Y un zorro).

Presentaremos el libro el 2 de mayo en Barcelona, el 9 de mayo en San Sebastián y en otras ciudades en los días siguientes. Cuando sepamos los detalles, los publicaré.

Feliz pedaleo.

cerrados

Eutyches y diez más

Xabi Prieto se retira. Traigo esta columna que publiqué el pasado 15 de febrero en El Diario Vasco, en la que yo ya me iba preparando.

EUTYCHES Y DIEZ MÁS

Me senté en un retrete emocionante. A la puerta le habían rebajado el ángulo superior izquierdo, para que pudiera abrirse sin rozar un arco de piedra. El arco formaba parte del circo romano de Tarragona, porque estas casas de la plaza de la Font están construidas así, aprovechando las bóvedas que sostenían el graderío. Así que, en el retrete de aquella cafetería, en la mismísima entraña del circo, imaginé que era un auriga nervioso, a punto de competir en la carrera de caballos. ¡Ya llaman las trompetas!

Del circo quedan una cabecera, la puerta triunfal, parte del graderío, galerías bajo las casas de Tarragona. Y lo más conmovedor: las lápidas de Eutyches y Fuscus, dos aurigas que murieron jóvenes. Los partidarios de la facción azul (los peñistas de la época) tallaron palabras para homenajearlos: eran diestros con las riendas, lucharon y no temieron, fueron amados por la afición, vivieron bellamente, el hado tuvo celos y se los llevó. “Derrama flores sobre sus restos, como cuando les aplaudían en vida”, nos piden las lápidas al cabo de dos mil años.

Cuando mi madre se harta de tantísimo fútbol, se aferra a una esperanza estrambótica: la caída del imperio romano. “Si los gladiadores desaparecieron, también desaparecerá el fútbol, ¿no?”, nos dijo una vez cuando salíamos hacia Anoeta. A mí me da apuro, por ella, que estos días andemos arriba y abajo con el festival Korner, con el fútbol metido hasta las librerías y los teatros, y pienso que ojalá sepamos contar que en estos juegos banales hay un impulso quizá bobo pero muy humano. Que ojalá alguien entienda, dentro de dos mil años, nuestra necesidad de tallar esta frase: aquí jugó Xabi Prieto.

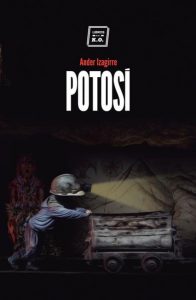

cerrados‘Potosí’ se publicará en inglés / ‘Potosí’ will be published in English

Dentro de unos meses, una editorial publicará ‘Potosí‘ en inglés. Tim Gutteridge, que ha sudado tinta para traducir los insultos de los mineros bolivianos -«mono culeao, cara de chuño, que te saco la puta»- y otro montón de bolivianismos, ha escrito esta presentación del libro:

In Potosí, Ander Izagirre tells the story of Alicia, a 14-year-old girl who lives on the slopes of Cerro Rico de Potosí, the mineral-rich mountain in Bolivia whose silver and other metals were a key source of wealth for the Spanish Empire from the 16th to the 19th centuries. Alicia shares an adobe-brick hut with her mother and younger sister on a windswept esplanade at the entrance to the mine which dominates their lives. The mining cooperative provides Alicia’s family with their makeshift home in exchange for her mother’s work guarding the equipment that is stored in a nearby hut; although Alicia is officially too young to be employed, she supplements the family income by working shifts in the mine, pushing a trolley full of rocks through underground tunnels for 2 euros a night. The toxic dust of the mine floats in the air they breathe and seeps into the water supply.

At the foot of the mountain, the city of Potosí, for so long a source of fabulous wealth, remains a place of immense poverty. Atlhough the rich seams of the past have all been exhausted, there are still over 10,000 people working in the mines (many of them children like Alicia) in small-scale, informal operations. They remove the rock by hand and transport it to the surface, where US and Japanese-owned multinationals grind it down and process it to extract the remaining ore. The resultant damage – both to the environment and to those who live and work in or near the mines – is devastating.

Izagirre skilfully uses this intimate portrait of a single family and the place where they live to tell a larger story: how the ‘blessing’ of mineral wealth has cursed Bolivia throughout its history, attracting the Spanish conquistadores who created a system of slave labour to extract the metal, and giving birth in the 19th century to a brutal local oligarchy that ruled over one of the poorest and most unequal countries on the planet. The country’s modern history has been marked by a series of military dictatorships, often installed with US backing with the express purpose of guaranteeing the flow of raw materials, and the economy remains extremely vulnerable to any fluctuation in the prices of tin and other minerals.

At the same time, this is a narrative that is not afraid of confronting uncomfortable truths, and Izagirre shows how the terrible working conditions and appalling safety record of the mines have not only caused the deaths of hundreds of thousands of miners through the centuries, but have spawned a patriarchal social system in which the miners, brutalised and traumatised by their experiences and numbed by alcohol, pass this on to their wives and children in the form of violence and physical and sexual abuse. This system has its symbolic focus in the figure of El Tío, a diabolic subterranean male counterpart to Pachamama, the Andean earth goddess, and goes hand in hand with active attempts to exclude women from the public and political spheres.

Although the story of Alicia and her family are at the centre of Izagirre’s account, he interweaves it with accounts of the lives of several other people: Pedro Villca, at 59 an ‘improbably old’ miner who is the author’s guide in the mines; Father Gregorio, an Oblate priest from northern Spain who was sent to Bolivia in the 1960s to run a Catholic radio station, and was hounded by the authorities for siding with the poor; Che Guevara, who died in a doomed attempt to light the fuse of a peasants’ and workers’ revolution in Bolivia; and Klaus Barbie, the Nazi fugitive who took refuge in Bolivia and put his skills to use by organising death squads on behalf of the CIA-backed dictator, General Barrientos.

The result is a uniquely engaging mixture of memoir, reportage, travel writing and history that is reminiscent of Ryszard Kapuściński at his peak.

Originally published by Libros del K.O. Details of UK publisher, dates and title coming shortly…

*

Excerpt 1

“A woman can’t enter the mine,” Pedro Villca tells me. “Can you imagine? The woman has her period and Pachamama gets jealous. Then Pachamama hides the ore and the seam disappears.”

Villca is an old miner, an unlikely combination in Bolivia. He’s 59 and none of his comrades have made it to his age. He’s alive, he says, because he was never greedy. Most miners work for months or even years without a break. Most miners end up working 24-hour shifts, fuelled by coca leaves and liquor, a practice for which they have invented a verb, veinticuatrear: ‘to twenty-four’. Instead he would come up to the surface, go back to his parents’ village for a few months to grow potatoes and herd llamas, fill his lungs with clean air to flush the dust out of them, and then go back to the mine. But he was never there when his companions were asphyxiated by a pocket of gas or crushed by a rockfall. He knows he’s already taken too many chances with death and that he shouldn’t push his luck. So he’s decided to retire. He swears that in a few weeks’ time he’ll retire.

Excerpt 2

Alicia opens her fist and shows me three stones the colour of lead, speckled with sparkling spots: particles of silver. She has pilfered them from the mine.

She wraps the stones in newspaper, puts the package in her backpack and disappears behind the canvas sacks to change her clothes. She takes off the overalls and puts on some jeans, a blue tracksuit top and a knitted hat. She grabs the backpack, and we leave the hut and walk downhill.

She’s 14 years old, and her hands are dry and tough, bleached by the dust of the mountain.

The wind sweeps the slopes: fragments of rock scatter before it, the rubble groans. The dust of Cerro Rico gets in your eyes, between your teeth, into your lungs. It contains arsenic, which causes cancer, and it contains cadmium, zinc, chrome and lead, all of which accumulate in the blood, gradually poisoning the body until it is exhausted. The dust also contains silver: between 120 and 150 grams of silver for every ton of dust. Every visitor takes away a few particles of Potosí silver in their lungs. It’s because of these particles, the need to separate them from all the others, that Alicia lives in an adobe hut on the mountain.

cerrados